7.1. Small Blocks

Aus Pattern Language Wiki

Within the network of Walkable Multi-Mobility, there is a scale of block patterns that is most conducive to walking.

❖ ❖ ❖

Problem-statement: Blocks that are too big create street networks that are unwalkable. But there is a practical limit to how small a block can be.

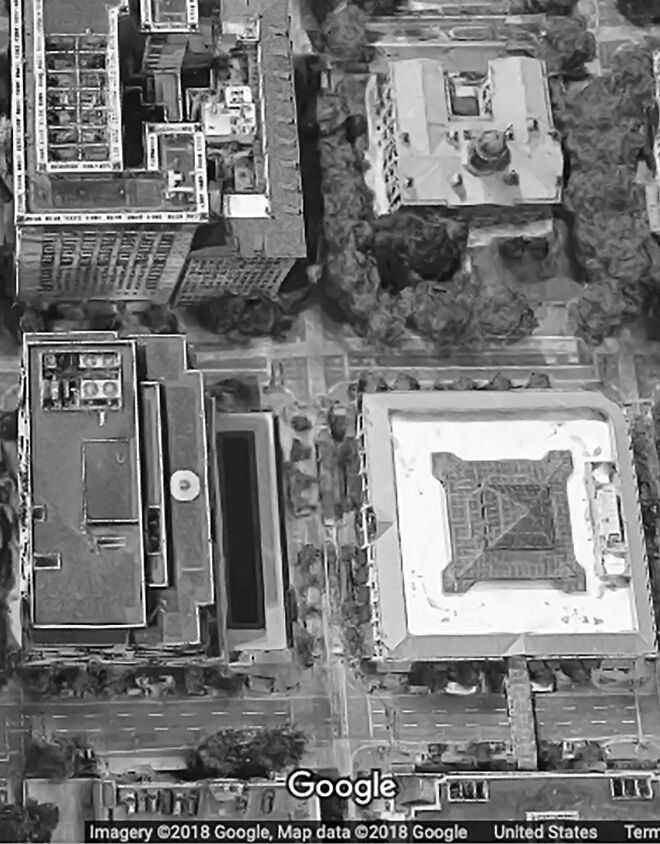

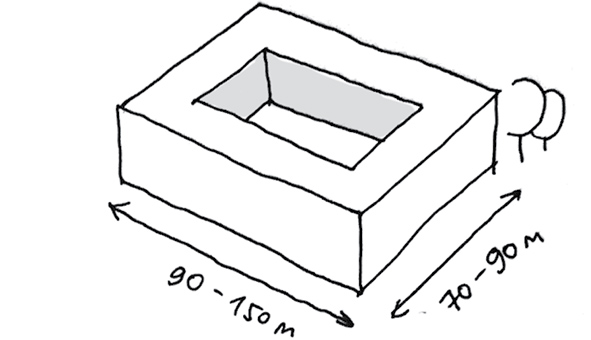

Discussion: Blocks that are smaller than about 60 meters in any one direction (about 200 feet), exclusive of the street right of way, create problems for accommodating outdoor space or alley conditions within the blocks. A more optimal minimum dimension is about 70 meters (230 feet).

But blocks that get much larger than double this distance in their longest dimension — about 150 meters or 500 feet — begin to create long pathways for pedestrians that discourage walking.

Jane Jacobs, in her landmark The Death and Life of Great American Cities, argued that small blocks are one of the four most important factors in generating diversity, in turn the most essential ingredient of great cities. She noted that long blocks disrupt the “intricate pools of fluid street use” that are necessary to support diverse economic and cultural interactions, and to maintain a “fabric of intimate economic cross-use”. In addition, shorter blocks help to generate more visual interest and more attractive walking experiences. Jacobs suggested that a block size much greater than about 400 feet (about 120 meters) was problematic.

Recent research has tended to confirm these insights, but added some nuance to the picture. One of the complicating factors is that block size need not be the same in length and width, and indeed may be irregular. Where one dimension is shorter, another dimension may be longer, and still result in an overall walkable form.¹

Smaller block size is also correlated with a denser street pattern, which has also been shown to be beneficial for walking and multi-modal transportation as well as active living and health outcomes.²

Yet another factor is the overall pattern of street connectivity, in which smaller block size plays an important role in promoting greater connectivity. Hillier and his associates have developed a “space syntax” model for street design, in which it can be shown that “natural” pedestrian movements (including those to commercial destinations) are dependent on “global properties of the street grid”. This is a confirmation of Jacobs’ insight that block sizes affect economic patterns and interactions.³

Unfortunately, today many commercial forces push towards gigantism, with the result that blocks of correct size have been amalgamated into large superblocks in many parts of the world, with their essential fine grain of streets removed. The result turns out to be negative for the users, and for the city as a whole (and perhaps positive only for the real estate speculators). For as we have seen, such an out-scale disruption strains and often damages the urban fabric, not only on the site and in the immediate vicinity, but also throughout the surrounding area. Jacobs memorably referred to the destructive edges of these superblocks as “border vacuums.”

Therefore:

Lay out blocks so that their shortest dimensions are roughly 70 meters (230 feet) and no more than 90 meters or approximately 300 feet. Make their longest dimensions no more than about 150 meters or 500 feet.

Create a mix of block sizes using Small Plots within regulated parameters. Use the Perimeter Building pattern at the edges of the blocks. …

¹ The correlation of smaller block size with walkability was later demonstrated by a number of researchers. See for example Moudon, A. V., Lee, C., Cheadle, A. D., Garvin, C., Johnson, D., Schmid, T. L., & Lin, L. (2006). Operational definitions of walkable neighborhood: theoretical and empirical insights. Journal of Physical Activity and Health, 3(s1), S99-S117. Additional nuance came from a study by Sevstuk and colleagues, suggesting that there are tradeoffs from smaller blocks, and that it is possible to be too small — see Sevstuk, A., Kalvo, R., & Ekmekci, O. (2016). Pedestrian accessibility in grid layouts: The role of block, plot and street dimensions. Urban Morphology, 20(2), 89-106.

² See for example Marshall, W. E. & Garrick, N. W. (2010). Effect of street network design on walking and biking. Transportation Research Record, 2198(1), 103-115. The same authors looked at data for traffic safety and also found a benefit: Marshall, W. E., & Garrick, N. W. (2011). Does street network design affect traffic safety?. Accident Analysis & Prevention, 43(3), 769-781.

³ See Hillier, B., Penn, A., Hanson, J. Grajewski, T., & Xu, J. (1993). Natural movement: or, configuration and attraction in urban pedestrian movement. Environment and Planning B: Planning and Design, 20(1), 29-66.

Mehaffy, M. et al. (2020). SMALL BLOCKS (pattern). In A New Pattern Language for Growing Regions. The Dalles: Sustasis Press. Available at https://pattern-language.wiki/.../Small_Blocks

SECTION I:

PATTERNS OF SCALE

1. REGIONAL PATTERNS

Define the large-scale spatial organization…

1.4. 400M THROUGH STREET NETWORK

2. URBAN PATTERNS

Establish essential urban characteristics…

3. STREET PATTERNS

Identify and allocate street types…

4. NEIGHBORHOOD PATTERNS

Define neighborhood-scale elements…

5. SPECIAL USE PATTERNS

Integrate unique urban elements with care…

6. PUBLIC SPACE PATTERNS

Establish the character of the crucial public realm…

7. BLOCK AND PLOT PATTERNS

Lay out the detailed structure of property lines…

8. STREETSCAPE PATTERNS

Configure the street as a welcoming place…

9. BUILDING PATTERNS

Lay out appropriate urban buildings…

10. BUILDING EDGE PATTERNS

Create interior and exterior connectivity…

10.1. INDOOR-OUTDOOR AMBIGUITY

SECTION II:

PATTERNS OF MULTIPLE SCALE

11. GEOMETRIC PATTERNS

Build in coherent geometries at all scales…

11.2. SMALL GROUPS OF ELEMENTS

12. AFFORDANCE PATTERNS

Build in user capacity to shape the environment…

13. RETROFIT PATTERNS

Revitalize and improve existing urban assets …

14. INFORMAL GROWTH PATTERNS

Accommodate “bottom-up” urban growth…

15. CONSTRUCTION PATTERNS

Use the building process to enrich the result…

SECTION III:

PATTERNS OF PROCESS

16. IMPLEMENTATION TOOL PATTERNS

Use tools to achieve successful results…

16.2. ENTITLEMENT STREAMLINING

16.3. NEIGHBORHOOD PLANNING CENTER

17. PROJECT ECONOMICS PATTERNS

Create flows of money that support urban quality…

17.4. ECONOMIES OF PLACE AND DIFFERENTIATION

18. PLACE GOVERNANCE PATTERNS

Processes for making and managing places…

18.3. PUBLIC-PRIVATE PLACE MANAGEMENT

19. AFFORDABILITY PATTERNS

Build in affordability for all incomes…

19.1. INTEGRATED AFFORDABILITY

20. NEW TECHNOLOGY PATTERNS

Integrate new systems without damaging old ones…

20.2. RESPONSIVE TRANSPORTATION NETWORK COMPANY